5 Dividend Stocks that can Help Your Portfolio Fight Inflation (12-Year Charts)

Barron’s — Inflation has been tame for so many years that it now ranks near the bottom of Wall Street’s list of worries. That could be a problem.

Barron’s — Inflation has been tame for so many years that it now ranks near the bottom of Wall Street’s list of worries. That could be a problem.

With the U.S. economic expansion in its ninth year and the labor market tightening, it’s only a matter of time before prices start to rise, threatening corporate profit margins—and stock prices. “We’ve gotten to the point in the economic cycle where inflation risk is meaningful,” says Ronald Temple, head of U.S. equity at Lazard Asset Management. “Any wisely constructed portfolio ought to include some component of inflation protection.”

There are many ways for companies to weather inflation. A strong balance sheet, ample cash flow, and fat profit margins afford a running start. An ability to raise prices helps, too.

And a nice thing about firms with those attributes is that their stocks tend to be good investments for any economic storm, regardless of moves in the consumer price index.

FRETTING ABOUT INFLATION NOW might seem beside the point, given that the CPI—a key U.S. inflation measure—has averaged an increase of only 2.2% a year from 2000 through 2016. But May’s 4.3% unemployment rate, the lowest reading in 16 years, could be sending a different message. A tightening labor market “usually coincides with a tight economy, and tightening in the economy leads to increased pricing power for output prices,” says Jim O’Sullivan, chief U.S. economist at High-Frequency Economics.

The identified five companies that could thrive in an inflationary environment, given their pricing power or interest-rate sensitivity. All five— Bank of America (BAC), Becton Dickinson (BDX), options exchange operator CME Group (CME), Johnson & Johnson (JNJ), and Royal Dutch Shell (RDS.A)—have solid fundamentals and the ability to increase their dividends by more than the rate of inflation.

While it may not be imminent, inflation should be on investors’ radar because, by the time it’s here, it will already be too late.

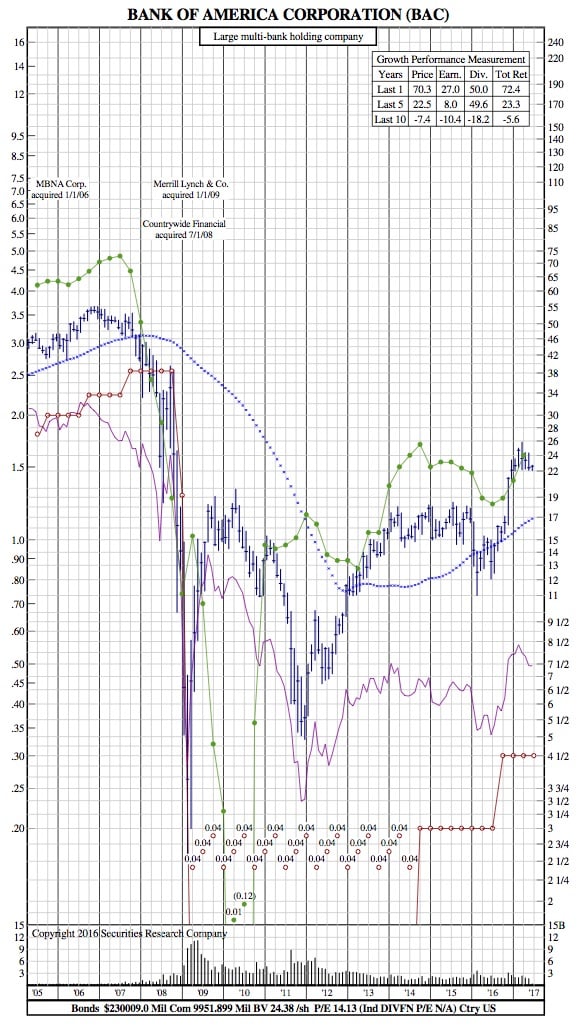

Bank of America

The second-largest U.S. bank by assets has struggled to recover from the recession, particularly the housing crisis. But things are finally showing signs of turning around.

The company earned 41 cents a share in its first quarter, up from 21 cents a year earlier, on a 14% revenue gain to $22.2 billion, helped by a 2% increase in loans and leases. Analysts are looking for the bank, which has $2.25 trillion in assets, to earn $21 billion, or $1.82 a share, this year, a 21% increase from 2016’s per-share profits.

The stock, recently at $23, yields a modest 1.3%, but the bank has been steadily increasing its payout. “They have a tremendous amount of operating leverage, shifting from a credit improvement story to an earnings-growth story,” says Mark Freeman of the Westwood Income Opportunity Fund.

The bank is considered one of the most sensitive to rate increases among its peers, partly owing to its $1.3 trillion of deposits, a third of which were parked in noninterest-bearing checking accounts, as of March 31. If rates move up further, as is probably the case under higher inflation, the spread between what the bank earns on its assets and what it pays on its liabilities, including deposits, would widen, boosting its net interest income. In addition, its huge portfolio of mortgage-backed securities would profit handsomely from higher rates.

The U.S. Federal Reserve is widely expected to lift rates this month.

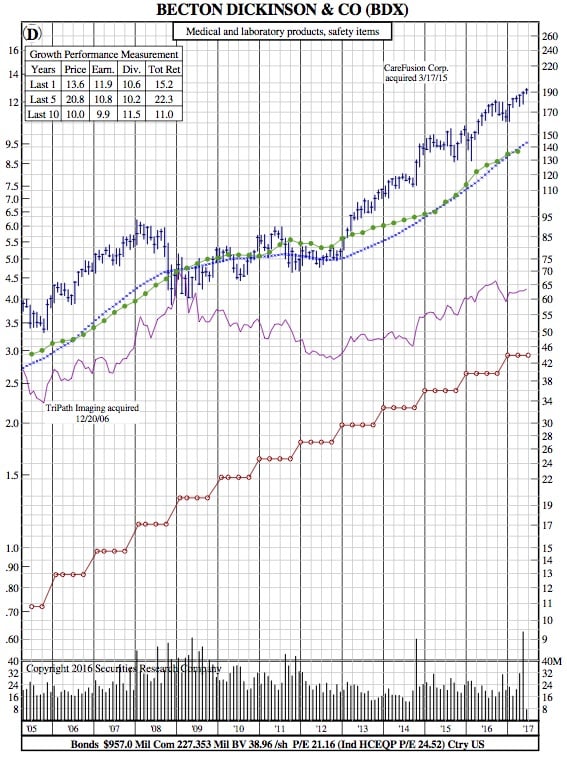

Two years ago, Becton Dickinson made a big bet when it acquired CareFusion, whose product suite included infusion pumps and drug-dispensing equipment, for $12.2 billion in cash and stock—by far the largest deal Becton had ever pulled off.

That seems like a middling acquisition now. In April, the company announced it would buy C.R. Bard (BCR) for $24 billion. Bard’s products include implantable heart devices and catheters.

Additionally, “Bard’s presence in oncology, urology, and infection-prevention products should immediately enhance [BD’s] portfolio of medical surgical products,” Alex Morozov, a Morningstar analyst, wrote shortly after the deal was announced. BD is expected to earn $1.7 billion, or $9.45 a share, this year on $12 billion in revenue. The shares, recently trading at $190, fetch 20 times earnings per share, which are expected to climb 9.8%. The stock yields 1.5%.

Although BD sells some sophisticated and expensive equipment, its revenue still relies on a lot of basic hospital products, such as safety needles and syringes. So it should be able to pass along price increases. “There would be a lot less pushback on Becton taking some pricing than, say, a medical-device company selling more-expensive products,” says Prashant Inamdar, an analyst and portfolio manager at Westwood Holdings Group. These products are relatively inexpensive but are still critical equipment that isn’t commoditized.

Late last year, the company raised its quarterly dividend by 11%. More increases are expected. “We remain committed to increasing the dividend,” the company’s chief financial officer, Chris Reidy, said when the C.R. Bard acquisition was announced.

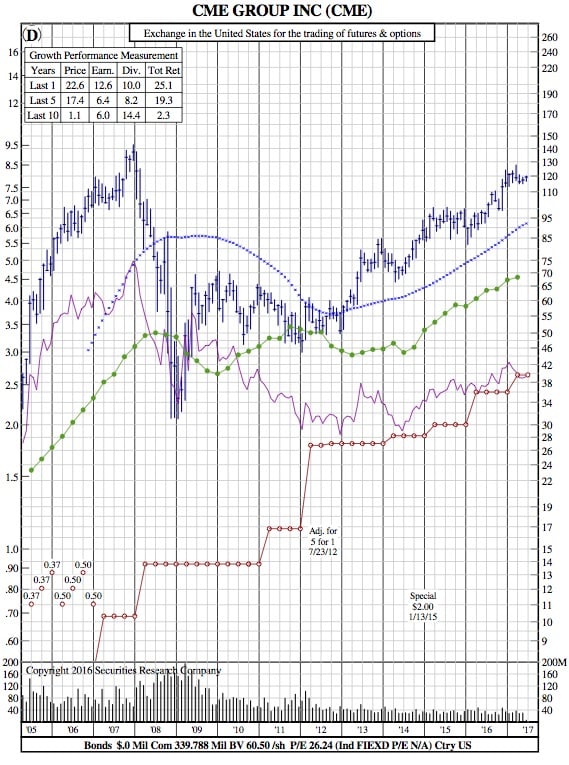

CME Group

Higher inflation will probably help Chicago-based CME, which operates exchanges for derivatives, notably futures and options. That’s because its products are prime financial hedging tools.

“As rates start to go up, the ability for investors to hedge on either side of the yield curve is a benefit for CME,” says Michael Barclay, a portfolio manager of the Columbia Dividend Income fund. Last year, about half of CME’s daily volume for contracts came from interest-rate products, followed by equities (20%) and energy (16%).

“Volatility is their friend, whether it’s from rates or commodities,” Barclay adds. Or, for that matter, equities, agricultural commodities, foreign exchange, or precious metals—all of which CME offers exposure to via its futures and options.

Analysts expect the company to earn $1.6 billion, or $4.84 a share, on $3.7 billion in revenue. Earnings per share are forecast to reach $5.26 this year, up 7% from $4.53 in 2016, with a nearly 10% boost next year, to $5.26 a share. The shares trade at $117 and yield 2.3%.

In February, the company increased its annual dividend by 10%, to $2.64 a share. The company has paid two special dividends totaling $6.15 a share since early last year.

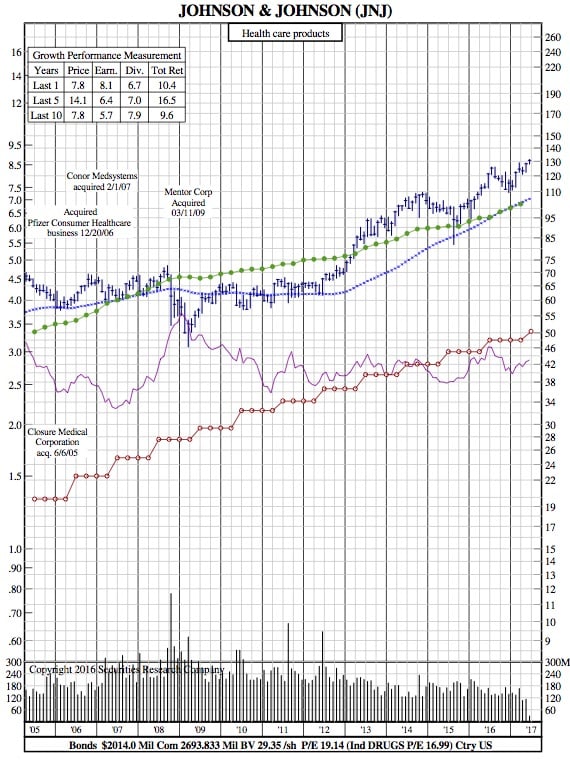

Johnson & Johnson

With its 2.6% yield, this triple-A-rated health-care conglomerate is already an attractive option for income seekers. And its diversified portfolio of businesses should allow the company to keep its dividend growing faster than inflation. Says Scott Davis, a portfolio manager and head of income strategies at Columbia Threadneedle Investments: “There’s nothing that says they can’t keep growing the dividend at 6% per annum over the next five years.”

Davis also notes that higher inflation can hurt stocks with high price/earnings ratios, but Johnson & Johnson trades at a market multiple of about 18.1 times the $7.10 that analysts expect it to post in earnings this year. He calls it “reasonably valued.”

J&J has an operating profit margin of about 30%, and it should generate a record $19.7 billion of free cash flow this year, up sharply from 2016.

That should keep the dividend growing comfortably, with plenty left over to buy back shares.

J&J has a balanced portfolio of assets to support its growth. Nearly half of its $72 billion of revenue last year came from pharmaceuticals, 35% was from medical devices and diagnostics, and just over 18% was driven by consumer products, including baby shampoo, Motrin, and Band-Aids.

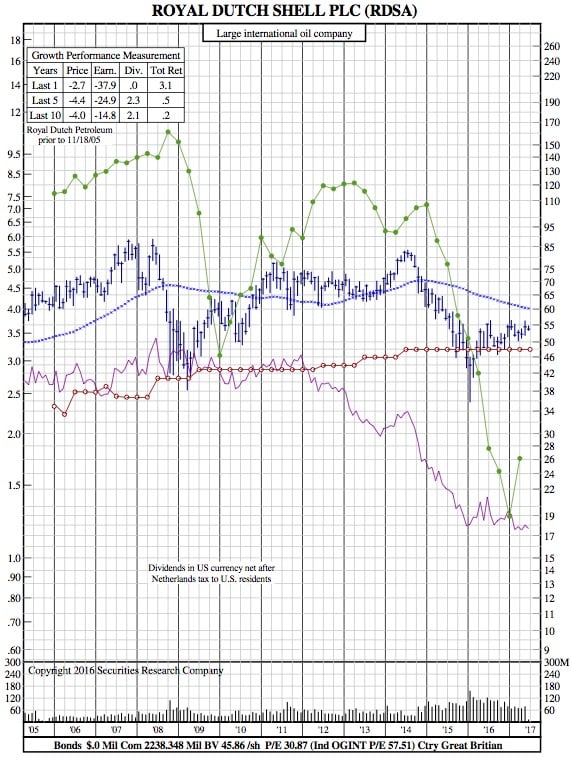

Integrated oil major Royal Dutch Shell should do well if inflation increases to a moderate level, say 3% or a little higher. In the meantime, it’s holding its own, having pulled back its capital expenditures due to lower energy prices.

The company is expected to earn $15.3 billion this year—up more than threefold from last year—or $3.44 a share, on revenue of nearly $300 billion.

Jason Brady, a portfolio manager of the Thornburg Investment Income Builder fund, says the firm would benefit from “good inflation, which is basically driven by tighter supply, demand for goods and services, and global growth.” Real assets such as oil, real estate, or gold often serve as a hedge against inflation.

Royal Dutch shares, which struggled in 2014 and 2015 after oil and gas prices collapsed, have rebounded somewhat, having gained over 10% in the past year. In its most recent quarter, its American depositary receipts earned 92 cents a share, up from 43 cents a year earlier. At a recent $54, they yield 5.9%.

Faced with much lower oil prices, the company has been able to adapt, as the earnings results show.

“What you’ve seen across the integrated oil names is that this downturn was very difficult for them to stomach,” says Matt Burdett, an associate portfolio manager of the Thornburg Investment Income Builder fund. “You’ve seen a real change in how they’re running their businesses to be more efficient.”

That means lower capital expenditures, which for Royal Dutch totaled about $22 billion last year, down from about $32 billion in 2014, according to FactSet.

But even with lower oil prices, which were about $50 a barrel recently, the company is on track to generate about $45 billion of operating cash flow this calendar year, estimates Burdett. That leaves plenty of cash to support the dividend.